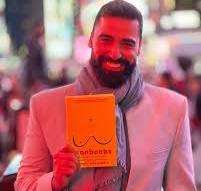

'Manboob's:' Growing Up Gay in Pakistan -- And Then to U.S.

When queer visual artist and writer Komail Aijazuddin was growing up in Lahore, Pakistan, he knew he was attracted to boys. But it wasn’t easy being gay. At his all-male prep school where, as an overweight, effeminate kid who loved “The Little Mermaid,” he was frequently bullied for his “manboobs.”

So as a youth he believed his only chance at a happy life would be found in America, where he believed freedom rings and gays live in an all-accepting, non-judgmental existence. But he discovered that a post-9/11 life for a dark-skinned man from Pakistan who did not fit into the physical gay ideal, was not quite what he imagined — and his personal issues, questions and doubts were still part of his baggage.

In his humorous, coming-of-age book “Manboobs: A Memoir of Musicals, Visas, Hope, and Cake,” Aijazuddin with wit and frankness reflects upon his coming out, and examines the American dream, his struggle with body issues and his finding self-acceptance as well as his place in the world.

Responses to the book (Abrams Press, 251 pages, $27; $20.99 Amazon) have been glowing: Publishers Weekly found the memoir “[A] sterling debut . . . Aijazuddin combines blazing wit with heartbreaking candor as he recounts his path toward self-acceptance as a gay Pakistani.” Kirkus Reviews calls ther book “a poignant reflection on identity, race, and the meaning of home. A wickedly funny and often moving memoir.” Perhaps the most special appreciation came from author Edmund White who called it “one of the funniest books I’ve ever read.”

Aijazuddin, 40, is a graduate of New York University in art and art history and holds an MFA from Pratt Institute. He now lives and works in New York City. He was vacationing in Fire Island when I spoke with him about the book.

“My story is not extraordinary but the way I tell it is,” he said over a FaceTime chat.

It’s a story of a queer man who was “too gay for Pakistan and too Muslim for America.”

“In the West in general, I am acutely aware that I am seen as a brown, bearded man before I am seen as anything else,” he said. “So one of the things that I wanted to do with the book was to talk about things that may seem to be completely unfamiliar to [the Western reader], but, in a way, that is cheeky.”

In the memoir Aijazuddin playfully speaks of being an effeminate young boy tricking his cousins into “making” him play with dolls. He writes about his love of “The Golden Girls, ” Broadway musicals and his crush on Colin Farrell (“mostly because of his eyebrows”). Aijazuddin also writes that the only representation he saw of himself in popular culture was in “Aladdin.” ("Just having something or someone that looks familiar to you was such a powerful thing.”)

As a gay man growing up at that time Aijazuddin writes about how he and other queer men maneuvered through early life, despite not being taught “the rituals of growing up, from courtships, to friendships, to family interactions” and instead suffered “a thousands cuts you go through life as a queer person in which a straight person would not experience.”

When his dream of coming to the U.S. came true, he quickly discover that it was far from “the gay promised land.”

“I was naive when I came here,” he said. “America has many of the same issues I faced [in Pakistan]. “One of the impulses I had to write the book was to show that despite my best efforts I could not be seduced by America and its idea of exceptionalism. Both countries were equally rejecting.”

“The truth is that people have the same difficulty in coming out here than they do anywhere else in the world,” said Aijazuddin, now a citizen. “The idea that we are somehow safer here is more hope than fact. We know now there are people here who want to attack us and take away our rights in the same way that do there so I wanted to to talk about gay rights from a global perspective.”

Part of that perspective is an acute awareness of political dangers.,

“I know what happens when a group of fascists emerge — and I’m saying this with humility and hope. I think if you grow up in a place without fascism or obvious references to fascism or totalitarianism, it can be easier to spot when it starts to happen compared to those who didn’t grow up in that environment.

“Gay men of an older generation can see it because they witnessed it,” said Aijazuddin . “But a lot of younger gay men who have grown up with the law on their side, well, I hope Americans can see what is happening now.”

Despite the painful adolescent coming-of-age and coming-to-the-U.S. stories (especially at the immigration offices and incidents of Islamophobia), it is also a very funny book, too.

“I didn’t want it to be preachy,” he said. “I believe if you can root something in humor and the moment you can make someone laugh, then you’ve got someone on your side.”

I asked him about the reaction from his family — especially his parents — since the book came out. “Their response has been measured,” he said. “Things are slightly quiet at the moment. I think it’s been an overwhelming experience for them. The only parts I write about them — or anyone in the book — are the parts that intersected with my actuality. There was a lot that was left out.

“It was not meant to be a big book of grievances but I wanted to be honest and and open about the fact that it wasn’t an easy journey for me. Yet even acknowledging that felt like such a betrayal on my part,” he said. “It took a lot to therapy to get to a point where I realized that I’m telling my own story and happiness can sometimes exact a price. I have come to terms with it all but, as I write at the end of the book, acceptance is not the destination. It’s something you have to do every day.”

To learn more about Aijazuddin and his art, visit komailaijazuddin.com.

###

An except from “Manboobs: A Memoir of Musicals, Visas, Hope, and Cake” by Komail Aijazuddin

“No one ever talked about being gay at all, really, even though I saw more homosexual desire around me than not. It was perfectly normal, for instance, to see two boys at school or two men on the street in Lahore walking together with their hands intertwined like lovers. For an unmarried heterosexual couple to do the same was, by comparison, nearly unthinkable. College professors later called places like Morocco, Pakistan, and India “homosocial environments,” societies where the cultural separation of genders meant public affection between men became an act of social conformity to segregation rather than any conscious declaration of an individual sexual identity. In places like these, the segregation confers a sense of plausible deniability on homosexual relationships. After all, hiding in plain sight is one of the ways that queer people can live with some measure of agency in repressive states the world over (how else do you think we got through the Middle Ages?). How can you be gay where gayness doesn’t exist?”

“This lazy conceit works right up until boys are expected to marry, which is usually when things fall spectacularly to pieces. Most of the gay men I know in Pakistan, even Western-educated, quasi-liberal ones living in the twenty-first century—unclench, I’m not outing you—are intent on marrying women. These men rarely call themselves gay (though enough of their ex-wives do) because to do that would require an acknowledgment of a reality they’ve worked extraordinarily hard to deny. “